When QE Goes Global: Why Macroprudential Tools Scale Better Than Capital Controls by Haiqin Liu

On major central-bank announcement days, financial markets often move far beyond the borders of the country making the decision. When the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank, or the Bank of England surprises markets—whether by changing interest rates or by buying assets at large scale—equity prices abroad can jump (or drop) within hours.

For policymakers in smaller open economies, this creates a practical question: when global monetary conditions change overnight, which “defenses” actually work? Should countries rely on capital controls, exchange-rate flexibility, or macroprudential regulation (rules that limit leverage and risky borrowing)? And do these tools keep working when unconventional monetary policy arrives in repeated, larger waves?

In my job market paper, I show that the answers depend on which type of external shock hits (conventional rate moves versus QE), and that macroprudential tools remain effective as QE scales up, while the marginal insulation from capital controls fades.

The usual trilemma—until balance sheets matter

The classic open-economy trilemma says you cannot simultaneously have (i) a fixed exchange rate, (ii) free capital mobility, and (iii) independent monetary policy. In a world of deep financial integration, this logic is often paired with the “global financial cycle” view: even with flexible exchange rates, global risk appetite shaped by core financial conditions can transmit powerfully across countries (e.g., Rey (2015)).

For conventional interest-rate shocks by major central banks, the trilemma intuition works well: tighter capital controls and/or more exchange-rate flexibility tend to reduce adverse spillovers.

But quantitative easing (QE) is different. QE moves long-term yields and risk premia through portfolio and balance-sheet channels. That changes which domestic policies help—and how their effectiveness evolves as QE becomes larger.

What I do

My job market paper combines three ingredients.

First, I isolate unexpected monetary policy shocks from the Fed, ECB, and BoE using high-frequency market movements measured in minutes around policy announcements. This lets me separate conventional rate surprises from QE-type surprises.

Second, I hand-collect and precisely date major domestic policy regime changes in three areas: capital controls, exchange-rate arrangements, and macroprudential regulation. The emphasis is on economically meaningful regime shifts—changes that plausibly matter for markets—rather than small administrative tweaks.

Third, I study how these domestic regimes shape spillovers using daily equity returns for more than 130,000 listed firms across 61 countries (1995–2025). The key idea is simple: I compare how strongly foreign firms’ stock prices react to major-central-bank shocks before versus after a country changes one of these policy regimes.

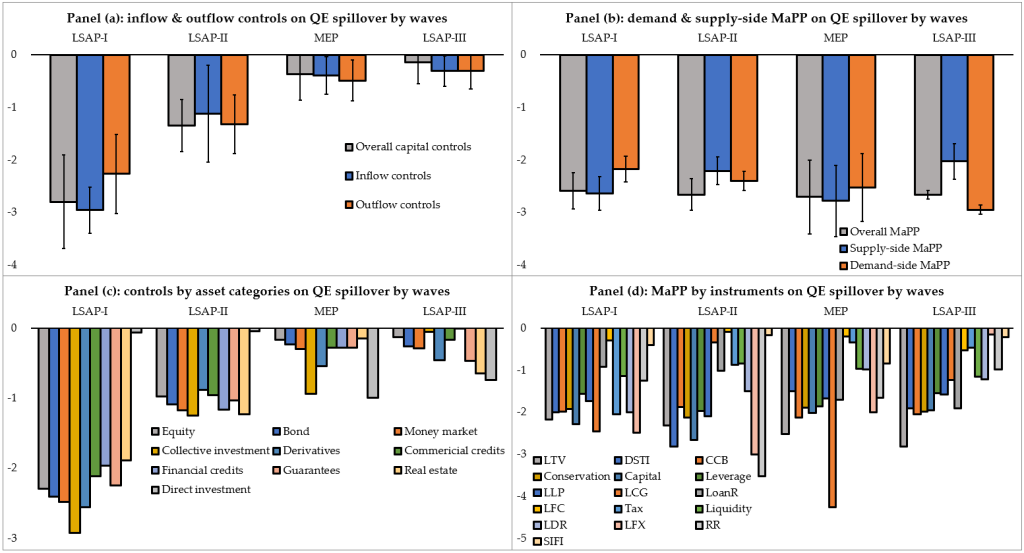

This design allows me to estimate (i) which tools moderate spillovers, and (ii) whether the moderation changes as QE scales up in successive “waves.”

What I find

I uncover three patterns with clear policy relevance.

1) Conventional rate shocks: Tighter capital controls or greater exchange-rate flexibility attenuate negative spillovers to foreign equity markets.

2) QE shocks: Exchange-rate flexibility tends to amplify spillovers. A plausible interpretation is that flexible exchange rates pass more valuation changes into balance sheets and cash flows—especially where foreign-currency liabilities (often in dollars) matter.

3) Macroprudential policy stands out: Macroprudential tightening mitigates spillovers from both conventional and QE shocks. More importantly, macroprudential tools remain effective as QE scales up, whereas the marginal shielding from broad capital controls declines quickly and then levels off.

To make this concrete: in early QE waves, both capital controls and macroprudential tightening can materially reduce foreign equity responses. But as QE becomes larger, the estimated additional insulation from capital controls falls to less than half of its initial impact, while macroprudential mitigation stays large—and in some specifications becomes stronger in later waves.

Why might macroprudential policy “scale” better than capital controls?

A useful way to think about the difference is what each tool directly targets (see also Korinek and Sandir (2016); Bergant, Grigoli, Hansen and Sandri (2023)).

Capital controls are often transaction-based (taxes, quantitative limits, approval requirements) on specific cross-border flows. They can slow surges in the short run, but as shocks intensify, investors and intermediaries may adjust by shifting across instruments, maturities, or jurisdictions—reducing the marginal bite of broad controls.

Macroprudential regulation operates on balance sheets. By limiting leverage, tightening FX-related borrowing, raising liquidity buffers, or constraining risky credit growth, it targets the mechanisms that turn global “risk-on” episodes into domestic booms and vulnerabilities. In that sense, it can dampen amplification rather than only redirect flows.

To interpret the empirical nonlinearities, I build a simple two-country model with collateral constraints. QE in the core economy loosens global financing conditions. In the model, capital controls act like a tax on cross-border transactions, while macroprudential policy acts like a leverage constraint that limits how much collateral can back borrowing. As QE becomes larger, the model helps explain why transaction-based frictions can lose marginal bite, while balance-sheet constraints can remain effective buffers against leveraged risk-taking and credit booms.

Policy takeaway

These results suggest a practical hierarchy for policymakers facing spillovers from major central banks.

- For conventional rate shocks, the classic trilemma logic remains a useful guide: capital-flow management and exchange-rate flexibility can reduce imported tightening.

- For QE shocks, policymakers should be cautious about assuming that floating exchange rates automatically provide insulation.

- If the objective is robust resilience across both conventional and balance-sheet shocks, macroprudential frameworks—especially those that directly target leverage and currency mismatch—appear to be a strong first line of defense.

What’s next

Two extensions matter for policy and research. First, I am expanding outcome measures beyond equities (e.g., credit spreads) to sharpen the link to risk premia. Second, I am enriching the theoretical framework to incorporate exchange rates to speak more directly to alternative exchange-rate arrangements under uncertainty.

About the Author

Haiqin Liu is a PhD candidate in the Elite PhD Program in Economics at Fudan University and a Consultant at the World Bank Group (East-Asia & Pacific Chief Economist Office and Job and Growth Unit).

Her research explores the nonlinear interactions between international policy regimes and multidimensional monetary policy spillovers. Visit her website: https://liuhaiqinfdu.github.io/

The views expressed here are the author’s and do not necessarily represent the World Bank Group.

Social Media Handles: